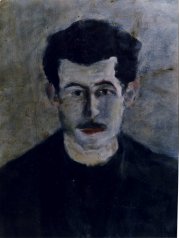

Esteban is a Spaniard of Catalan mother and Andalusian father. He grew up in a small Catalan city. He came from Barcelona to Paris with dreams of journalistic glory as an envoy of a literary magazine. He had the great sensitivity of a writer but for success he lacked two basic qualities: education and money. In Barcelona, the magazine published his rubric a la Dear Abby which he surely handled well because he knew how to dig into life situations and his religious morality concorded with that of his society. But he had ambitions for larger horizons and so he found himself in Paris. His task was to interview various stars of song and TV but he didn’t yet know enough French. He gave me his short stories to read, one of which made a deep impression on me. It spoke of a young painter who, after a conflict, left his family home and his little town and ended up in Barcelona with just a small sum of money. On a street corner he noticed a young attractive prostitute and with youthful carelessness he decided to spend his last penny on her. In the hotel room they had a friendly conversation and he told her his story. She told him, “My history is somewhat similar to yours. But for me it’s too late. Go back home to your father and mother before the Moloch of the big city also swallows you.” It was so warmly said and in such simple language that I felt the situation as if I were there. I said to Esteban, “I am impressed, you are a Spanish Balzac of simple things.” I should not have told him that. I wounded him by saying that he wrote about simple matters. To show that he could write about extraordinary matters he started to write cheapies about love and murder and he couldn’t understand why I didn’t like them. He probably suspected me of jealousy.

Esteban’s story, unfortunately, is also a story of defeat even though he resisted with admirable stubborness. His youth let him survive the Parisian winter which is stern though without snow. He would leave my place late in the evening, I didn’t know why he wore such a sour expression. Well, he was spending nights under the sky in some warm sewer among bums and degenerates. He knew how to keep the secret to himself. My wife remarked, “Why does Esteban stink? Doesn’t he change his clothes?” Once she encountered him on the street in this condition and told him, “Esteban, either put yourself together or go back to Spain.” He stayed with us for a few days, then he found work and a place to live. He became a cleaner at some public swimming pool.

At the beginning he still got letters from his editor but finally lost contact with his magazine. He was passing through life, always with his Chaplinesque smile, though he was no longer the same Esteban. He became sort of a cynic, he probably lost his religious morality, a dangerous step for a simple man. He claimed that he was satisfied and perhaps he really was. He’d say, “If I were offered an editorial position in Buenos Aires, I’d tell them to keep it for themselves!” He claimed that he didn’t want to lose contact with Europe but what was this Europe for him? Late at night after work, onion soup in Les Halles then — if he didn’t have a girlfriend — a prostitute. He eventually went to Spain with some money and got married.

#88 excerpt, 4 Portraits, July-August 2005